It was late September and Whit Hibbard was back to give a refresher seminar on the low stress livestock handling method and and teach park employees with some hands on experience. Whit brought his colleague, Samantha, who has studied the method and worked with Whit on the ranch and at Big Bend. We spent one day showing Samantha the park, the handling facility, and what horses we could find from the truck, talking strategy of which bands might be the best to approach and where would be the best place to try to pen them.

Friday morning was the short seminar where we were reminded of the main points of low stress handling: work with the animals, not against them, don't act like a predator, let our idea become the animal's idea, make the wrong thing difficult and the right thing easy with pressure and release. Personnel were able to practice the techniques with some domestic horses and cattle that afternoon.

Henry and I opted to ride out with Samantha to check out the sheep pen, make sure the gate was locked on the south side, lay a trail to the pen so that there would be fresh horse scent on the trail, and scout for the bachelors we had seen in the area the day before. We were able to find only one bachelor, but approached him to see how large his flight zone was. He was totally unconcerned with us, so we thought he would be a good option for another field trial to see if Whit could repeat the success he had with the L band earlier this year.

Since we wanted to find the five other bachelors we had seen with "Ollie," we spent the morning scouring the hills and valleys for about a mile either side of the river, but were not able to find any more horses. Whit took a couple hours to take the lone stud to the sheep pen, and with Samantha's help was able to pen him.

The next day we rode from the handling facility. I spotted High Star in the distance on Talkington Trail, so we rode to the north to get around him. While we were covering that distance, High Star and his band of seven moved to Lindbo Flats. We were able to approach them and shrink their flight zone some, but there were 39 other horses in the area, milling around and playing on that cool, windy day, so it was difficult to get the band to settle. Before we got very close to them, Pale Lady decided it was time to leave and even evaded High Star's attempt to head her off. We took a look at several other small bands on the flats and were able to move one small band of bachelors to the east, but then a large group of over 20 horses came toward Whit and Samantha, cutting around the ridge about 30 feet in front of them taking the bachelors with them. The whole 47 horses ran in circles as if to show us that they were to happy to be free and didn't want to cooperate with us.

The following day we tried another tactic, finding the horses from the loop road. Henry and I went out early and found four bachelors on Paddock Creek where the road crossed it. We were able to call Whit and tell them where to park to unload their saddled horses. We now had most of the day to move the small band down Paddock Creek Valley to either the Peaceful Valley Ranch pen or the sheep pen. We decided it was best to have only Whit and Samantha work with the horses and the rest of us including our friend, Laurie, from the North Unit, guide them from high vantage points along the way.

On this cool morning these bachelors were also feeling frisky, but after a time of acclimating them to his and Samantha's presence Whit initiated some movement down the valley to the west. I had told Whit that the trail started on the south side of the creek but then crossed and remained mostly on the north side the rest of the way to the river, so it was his plan to move them slowly along the bottom just south of the creek until he could cross them over to the north side. Suddenly the bachelors had other plans and ran up a valley to the south. Whit and Samantha followed them and were able to find them stopped on the high ground below the Badlands Overlook where another bay bachelor joined them. We were able to observe all this from a high butte from which we could call Whit and Samantha with locations of the horses and possible routes to try once they were able to move them again.

After some time of getting them to settle down, Whit attempted to move them again the to west. They went west initially, but since they had a bachelor from the B band with them, he wanted to go back to the east and turned them back. Whit was again able to follow them back east where they turned onto the loop road. With Whit trailing along behind, they followed it for several miles. We hadn't thought of such an obvious route to get from the rough country below Badlands Overlook to the relative rolling terrain of Johnson Plateau, but it certainly made the going easier for Whit and his horse.

Laurie and I went ahead, opened the ranch pen, and left her horse in an adjoining pen for bait, but the bachelors decided they wanted to go south and once they reached the river bottom, they headed straight for the sheep pen. Henry and I took off at a brisk trot for the sheep pen to get it open before the band reached it. Whit and Samantha held them up until we could get there and get out of the way. At one time a group of hikers frightened the horses up the ridge to the west and Whit thought they were gone, but they came back down. We joined Whit and Samantha about a half mile from the pen and shadowed them as we asked them to move again. The horses were at first wary of the additional riders, but accepted us and started down the trail. By that time the two lame bachelors had dropped out, so there were only three left. They were all used to running on the river bottom, so it was a familiar place to them. They moved quietly along the trail until they came to the wing fence which was made of plastic snow fence. If it was the fluttering, shiny snow fence of just the appearance having nowhere to go, I do not know, but they suddenly broke and ran for the river and through a thick stand of Cottonwood and Juniper. The day had been long and was coming to an end. Whit decided not to follow. We had failed to pen the additional bachelors, but was it really a failure? Whit had been able to move the horses several miles through rough terrain and bring them right to the mouth of the sheep pen. Maybe with a larger opening and better wing fencing we would get them in another time.

It was certainly an adventure Henry and I will never forget. We gained more respect for Whit's skills to be able to do what he had just done. We gained new respect for our horses, who had been up to the challenge of taking us safely across the rough terrain for four long days. We gained priceless experience and insight as to the effectiveness, but difficulty of using the low stress methods in this park and we gained two great new friends in Whit and Samantha. All in all it was a very successful five days.

Oh, yes, and Ollie? we let him go.

Saturday, October 4, 2008

Friday, September 19, 2008

Whisper's Story

It was a crisp fall day when I first saw her, a tiny sorrel overo filly romping with her bigger, blue roan brother. They bucked and reared together in the cool shadow of a large clay butte that kept the sunshine from reaching the river valley. Life was carefree for the two foals running through the tall green grass on the bank of the Little Missouri. The sun was still warm and the grass was still plentiful on that October morning, but the days were getting short and winter was not far away. God did not intend to have foals born in October; most of them were born in the spring or in the warm days of summer, but this little filly, with the big splashes of white on her sides and over her face and the promise of a flaxen mane fluttering in curly wisps down her neck, was less than a week old. She had no way of knowing of the brutal temperatures and relentless winds that would pummel the North Dakota prairie in just a few weeks. Those winds can barrel through the canyons like freight trains, freezing everything in their way. They freeze the river and water holes and bring snow that wets the hide and covers the rich grasses making every bite a chore. I wondered, would the newborn filly make it through a harsh North Dakota winter? I didn't see her that winter, so I could only guess about the safety of the filly and the two other late foals born that fall. I hoped that the snow would not be too deep and the temperatures not too severe.

The following spring I was anxious to check on the horses to see if all had survived. The winter had taken it's toll, but the cute overo filly was still with the L band, lounging in the protection of the great cottonwoods along the Little Missouri. The L band had a bad reputation for being pests in the park because of the home they had chosen. They found shelter in the brush and cottonwoods along the river bank where the wind didn't reach them in winter and the sun didn't scorch them in summer. They also found that the mowed grass of Cottonwood Campground was tender and green. They didn't mind that the lush grass was sometimes covered with a tent or a camper; they could share their home with visitors. What made them unwelcome was their discovery that the Redwood benches and signs in the campground were quite tasty. Being horses, they got bored once in a while and would find something to do that satisfied their chewing habit and tasted good too. The Park personnel had tried to run them out of the campground and even to capture them and send them away, but to no avail.

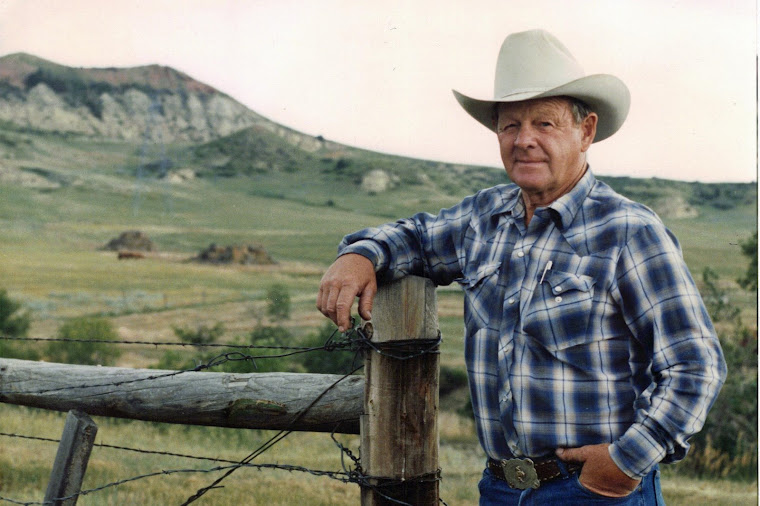

That spring the Park Superintendent, Valerie Naylor, contacted a low-stress livestock handler to teach the Park personnel some more effective ways to deal with animals who had escaped the park or the horses, whose numbers had made it necessary to sell some off so that vegetation in the Park would not be overgrazed. Whit Hibbard is a Montana rancher, who has learned the low-stress methods of Bud Williams and has used those methods successfully on his ranch and to capture trespass animals that have come across the Rio Grande into Big Bend National Park in Texas. Whit states that, "if done properly, low-stress livestock handling is more cost-effective and efficient, ethical and humane, and safer and easier for both people and animals than traditional livestock handling."

In early May Whit came to the Park and gave a seminar on low-stress livestock handling. Valerie graciously invited us to attend. The method uses many of the principles I was familiar with in natural horsemanship but on a much larger scale. Whit showed video of Bud separating and penning bull Elk and Reindeer as well as domestic livestock. He explained how one or two people could round up, pen, and load animals that would scatter with traditional methods. I found the methods fascinating and practical, but would they work with the wild feral horses of Teddy Roosevelt Park?

Whit had invited me to ride along with him the following day when he went to work with the L Band. All attempts to remove them from the area of the campground had failed, so he wanted to see if his methods might work. I showed up with a dressage horse, a dressage saddle, breeches, helmet, and a bitless bridle, but Whit wasn't quick to judge, he just asked, "Do you ever ride western?"

The river was raging from the rains that had been soaking the region for the past several days, so we loaded my horse and one of the Park's horses, that Whit was going to ride, into my trailer and drove to the other side of the river. We rode through the sheep pen, a sixty acre pen in the southwest corner of the park, that would be our destination if we were able to get directed movement from the horses. Just across from the campground, in a stand of young cottonwoods, we found the L Band.

Delicious was the band stallion of the L Band, having gotten his name because of what he would be in the frying pan of the trail riding concession providers if he didn't quit jumping in with their trail horses. His lead mare, Georgia, and three of the other mares were daughters of Curious George. He also had a nice blue mare that had been one of those to escape the storm and the roundup in 2003 by going across the river. There were 10 horses in all, four mares, two with new foals by their sides, a 2006 colt, a 2007 spring colt, and the little sorrel overo filly born in October.

Whit emphasized to me that the initial contact with the animals was of greatest importance; success or failure may be determined with the the animals' first sighting of an intruder. Since horses are prey animals, they are always ready to run if they think they are threatened. These horses had seen riders coming and going from the trial ride concession at Peaceful Valley Ranch, so they were not too concerned with us as long as we stayed at a distance. Whit asked me to shadow him and his horse since the horses would be less alarmed with seeing fewer riders. We approached them in a zig-zag pattern being careful not to penetrate too far into their flight zone, the distance at which they would feel threatened and run. Watching the most sensitive mare, Whit would move in and out of the flight zone on his passes by the band to get them used to us being there. I kept my gelding behind and beside Whit's so that they moved as one. Once the band was familiar with us and accepted our presence, it was not hard to put gentle pressure on them to push them in the direction we wanted them to go. With the river on one side and the high bluffs on the other, the horses slowly headed up the river bottom toward the sheep pen with Whit and me riding slightly behind and to the side of the band. Whit shared that he treated the band of ten horses like one horse, putting gentle pressure on one side toward the rear to encourage them to go forward or moving up toward the front to turn them. Once we separated to guide from both sides, but the horses were so accustomed to having us move as one that it frightened them and they ran for a ways toward the river. Patiently Whit repeated his zig-zag aproach and continued the slow progress toward the sheep pen. Within two hours we had the horses in the pen; we looked at one another and asked."What do we do with them now?"

We had been given radios, so Whit called in and, I am very sure, the winding down of that Friday afternoon took an abrupt U turn, and Park employees who were still in the office jumped to the task of finding panels and a trailer and developing a plan for 10 horses they really didn't think they would be dealing with in such a short time. While Whit and I practiced moving the horses through the corner of the sheep pen where a small pen would be built, Mike Oelher, Park Biologist, located and brought ordinary ranch panels and built a pen about 30 by 60 feet. Using the natural terrain, we were able to move the horse toward the corner into the pen and close the gate before they knew they were caught. Although the pen was small and not very high, the horses accepted it because they had not been frightened.

The next morning was loading time. Whit stood outside the pen to get the horse used to seeing him on foot and gradually worked his way into the pen. Before he even entered the pen, he had the blue yearling colt comfortable enough to come smell his hand. Once the horses were used to having someone in the pen with them, they were sorted into family groups and loaded into an ordinary stock trailer. What I found amazing was that, once the horses were ready to load, they stepped in and stood quietly. It took about and hour and 45 minutes to load the ten horses in two separate loads. The horses would be be held at the handling facility until Monday when they would be transported to the sales barn.

Only then could Whit and I revel in what had just happened. Wild feral horses had just been taken from the Park quietly, calmly, and safely; it had never happened before in the history of the Park. As we dismantled the panel pen, I put a tempting idea into Whit's head; I told him he should buy the blue colt, since he had it half gentled already. It took less than five minutes for the idea to take hold. What a unique opportunity, to own and train a horse that he had brought in from the wild.

Monday morning Whit wanted to give some Park employees the opportunity to work with the horses, but not until they had been brought through the long alleyway from the lower catch pen to the tub. This was the very task which had been so dangerous with the helicopter 6 months earlier, but with just Whit and I on horseback and anyone else watching from afar, the band walked quietly up the ally and into the tub. Whit loaded a family of three and had Mike load the next family. The stallion and the mare with the late filly were next. With my heart in my throat and a few wise words from Whit, I was able to load them onto a noisy aluminum trailer and send them on to a new chapter in their lives. It was bitter sweet because I did not know where they would end up.

The sales barn in Dickinson was a noisy place with horses huddling in pens and local ranchers sizing them up, but the wild horses took it all in without showing much fear. They had been handled with kindness so far; I could only hope they would find kindness in their future. When Whit arrived, we talked a little strategy and the sale began. Whit's colt was the second to come into the ring. He was the most popular one of the band because of his beautiful color and his age. I was afraid Whit would miss out on the bidding, and gave him a little nudge in the ribs. I would have bid for him, I was so excited for him to get the colt. In less than five minutes the colt was his. The colt could find no better home and Whit had a horse that would always be special to him. None of the other horses brought as much, but none were bought by the kill buyers.

The last to come through the ring was the little filly. Her eyes were huge with fright, but she didn't get crazy; she handled herself well, trusting that in this loud crowded place, no one would hurt her. The auctioneer wasn't getting a bid. Didn't anyone want to take home this cute little filly? OK, plan B went into effect; the auctioneer lowered the bid and I raised my hand. I had just purchased the filly I had watched play that cold October morning, worried about though the long cold winter, helped bring in from the bank of the Little Missouri, loaded onto a trailer with her sire and dam, and determined would not go to kill on my watch!

Whit named his colt Teddy, fitting for a brave young horse born wild in Teddy Roosevelt National Park. He lives in Montana now and Whit can't wait to ride him out with the other ranchers and have them admire that strong young horse with the dark blue coat. The cute overo filly lives with a Saddlebred gelding she thinks is papa, and a 17 hand dressage horse. Her name is Whisper because she was whispered from the park, not roared. She may look like any other spotted filly, but she was one of the first to be born in the wild and be literally walked off the Park in a low-stress roundup. She doesn't know, nor does she care, but she was a part of history.

I had to interrupt my introduction of the bands with Whisper's story because Whit is coming back to the Park. Will he be successful? We don't know, but we can hope that in the future horses can be brought in without danger and stress and in smaller numbers so that they too, like Teddy and Whisper, can find good homes and live purposeful lives.

The following spring I was anxious to check on the horses to see if all had survived. The winter had taken it's toll, but the cute overo filly was still with the L band, lounging in the protection of the great cottonwoods along the Little Missouri. The L band had a bad reputation for being pests in the park because of the home they had chosen. They found shelter in the brush and cottonwoods along the river bank where the wind didn't reach them in winter and the sun didn't scorch them in summer. They also found that the mowed grass of Cottonwood Campground was tender and green. They didn't mind that the lush grass was sometimes covered with a tent or a camper; they could share their home with visitors. What made them unwelcome was their discovery that the Redwood benches and signs in the campground were quite tasty. Being horses, they got bored once in a while and would find something to do that satisfied their chewing habit and tasted good too. The Park personnel had tried to run them out of the campground and even to capture them and send them away, but to no avail.

That spring the Park Superintendent, Valerie Naylor, contacted a low-stress livestock handler to teach the Park personnel some more effective ways to deal with animals who had escaped the park or the horses, whose numbers had made it necessary to sell some off so that vegetation in the Park would not be overgrazed. Whit Hibbard is a Montana rancher, who has learned the low-stress methods of Bud Williams and has used those methods successfully on his ranch and to capture trespass animals that have come across the Rio Grande into Big Bend National Park in Texas. Whit states that, "if done properly, low-stress livestock handling is more cost-effective and efficient, ethical and humane, and safer and easier for both people and animals than traditional livestock handling."

In early May Whit came to the Park and gave a seminar on low-stress livestock handling. Valerie graciously invited us to attend. The method uses many of the principles I was familiar with in natural horsemanship but on a much larger scale. Whit showed video of Bud separating and penning bull Elk and Reindeer as well as domestic livestock. He explained how one or two people could round up, pen, and load animals that would scatter with traditional methods. I found the methods fascinating and practical, but would they work with the wild feral horses of Teddy Roosevelt Park?

Whit had invited me to ride along with him the following day when he went to work with the L Band. All attempts to remove them from the area of the campground had failed, so he wanted to see if his methods might work. I showed up with a dressage horse, a dressage saddle, breeches, helmet, and a bitless bridle, but Whit wasn't quick to judge, he just asked, "Do you ever ride western?"

The river was raging from the rains that had been soaking the region for the past several days, so we loaded my horse and one of the Park's horses, that Whit was going to ride, into my trailer and drove to the other side of the river. We rode through the sheep pen, a sixty acre pen in the southwest corner of the park, that would be our destination if we were able to get directed movement from the horses. Just across from the campground, in a stand of young cottonwoods, we found the L Band.

Delicious was the band stallion of the L Band, having gotten his name because of what he would be in the frying pan of the trail riding concession providers if he didn't quit jumping in with their trail horses. His lead mare, Georgia, and three of the other mares were daughters of Curious George. He also had a nice blue mare that had been one of those to escape the storm and the roundup in 2003 by going across the river. There were 10 horses in all, four mares, two with new foals by their sides, a 2006 colt, a 2007 spring colt, and the little sorrel overo filly born in October.

Whit emphasized to me that the initial contact with the animals was of greatest importance; success or failure may be determined with the the animals' first sighting of an intruder. Since horses are prey animals, they are always ready to run if they think they are threatened. These horses had seen riders coming and going from the trial ride concession at Peaceful Valley Ranch, so they were not too concerned with us as long as we stayed at a distance. Whit asked me to shadow him and his horse since the horses would be less alarmed with seeing fewer riders. We approached them in a zig-zag pattern being careful not to penetrate too far into their flight zone, the distance at which they would feel threatened and run. Watching the most sensitive mare, Whit would move in and out of the flight zone on his passes by the band to get them used to us being there. I kept my gelding behind and beside Whit's so that they moved as one. Once the band was familiar with us and accepted our presence, it was not hard to put gentle pressure on them to push them in the direction we wanted them to go. With the river on one side and the high bluffs on the other, the horses slowly headed up the river bottom toward the sheep pen with Whit and me riding slightly behind and to the side of the band. Whit shared that he treated the band of ten horses like one horse, putting gentle pressure on one side toward the rear to encourage them to go forward or moving up toward the front to turn them. Once we separated to guide from both sides, but the horses were so accustomed to having us move as one that it frightened them and they ran for a ways toward the river. Patiently Whit repeated his zig-zag aproach and continued the slow progress toward the sheep pen. Within two hours we had the horses in the pen; we looked at one another and asked."What do we do with them now?"

We had been given radios, so Whit called in and, I am very sure, the winding down of that Friday afternoon took an abrupt U turn, and Park employees who were still in the office jumped to the task of finding panels and a trailer and developing a plan for 10 horses they really didn't think they would be dealing with in such a short time. While Whit and I practiced moving the horses through the corner of the sheep pen where a small pen would be built, Mike Oelher, Park Biologist, located and brought ordinary ranch panels and built a pen about 30 by 60 feet. Using the natural terrain, we were able to move the horse toward the corner into the pen and close the gate before they knew they were caught. Although the pen was small and not very high, the horses accepted it because they had not been frightened.

The next morning was loading time. Whit stood outside the pen to get the horse used to seeing him on foot and gradually worked his way into the pen. Before he even entered the pen, he had the blue yearling colt comfortable enough to come smell his hand. Once the horses were used to having someone in the pen with them, they were sorted into family groups and loaded into an ordinary stock trailer. What I found amazing was that, once the horses were ready to load, they stepped in and stood quietly. It took about and hour and 45 minutes to load the ten horses in two separate loads. The horses would be be held at the handling facility until Monday when they would be transported to the sales barn.

Only then could Whit and I revel in what had just happened. Wild feral horses had just been taken from the Park quietly, calmly, and safely; it had never happened before in the history of the Park. As we dismantled the panel pen, I put a tempting idea into Whit's head; I told him he should buy the blue colt, since he had it half gentled already. It took less than five minutes for the idea to take hold. What a unique opportunity, to own and train a horse that he had brought in from the wild.

Monday morning Whit wanted to give some Park employees the opportunity to work with the horses, but not until they had been brought through the long alleyway from the lower catch pen to the tub. This was the very task which had been so dangerous with the helicopter 6 months earlier, but with just Whit and I on horseback and anyone else watching from afar, the band walked quietly up the ally and into the tub. Whit loaded a family of three and had Mike load the next family. The stallion and the mare with the late filly were next. With my heart in my throat and a few wise words from Whit, I was able to load them onto a noisy aluminum trailer and send them on to a new chapter in their lives. It was bitter sweet because I did not know where they would end up.

The sales barn in Dickinson was a noisy place with horses huddling in pens and local ranchers sizing them up, but the wild horses took it all in without showing much fear. They had been handled with kindness so far; I could only hope they would find kindness in their future. When Whit arrived, we talked a little strategy and the sale began. Whit's colt was the second to come into the ring. He was the most popular one of the band because of his beautiful color and his age. I was afraid Whit would miss out on the bidding, and gave him a little nudge in the ribs. I would have bid for him, I was so excited for him to get the colt. In less than five minutes the colt was his. The colt could find no better home and Whit had a horse that would always be special to him. None of the other horses brought as much, but none were bought by the kill buyers.

The last to come through the ring was the little filly. Her eyes were huge with fright, but she didn't get crazy; she handled herself well, trusting that in this loud crowded place, no one would hurt her. The auctioneer wasn't getting a bid. Didn't anyone want to take home this cute little filly? OK, plan B went into effect; the auctioneer lowered the bid and I raised my hand. I had just purchased the filly I had watched play that cold October morning, worried about though the long cold winter, helped bring in from the bank of the Little Missouri, loaded onto a trailer with her sire and dam, and determined would not go to kill on my watch!

Whit named his colt Teddy, fitting for a brave young horse born wild in Teddy Roosevelt National Park. He lives in Montana now and Whit can't wait to ride him out with the other ranchers and have them admire that strong young horse with the dark blue coat. The cute overo filly lives with a Saddlebred gelding she thinks is papa, and a 17 hand dressage horse. Her name is Whisper because she was whispered from the park, not roared. She may look like any other spotted filly, but she was one of the first to be born in the wild and be literally walked off the Park in a low-stress roundup. She doesn't know, nor does she care, but she was a part of history.

I had to interrupt my introduction of the bands with Whisper's story because Whit is coming back to the Park. Will he be successful? We don't know, but we can hope that in the future horses can be brought in without danger and stress and in smaller numbers so that they too, like Teddy and Whisper, can find good homes and live purposeful lives.

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

The D Band

For many years a band ran in the area of Wind Canyon, feeding on the plentiful grass covering the rolling hills and river bottom of the farthest north western corner of the park. For a time, a stunted black stallion we called Tiny Tim had the band, but he was soon replaced by a pretty bay roan, Wind Canyon.

Until the late 1990's, Wind Canyon ran unchallenged, but in 2000 a plain black stallion picked up a few of his mares and fillies. We called that stallion Black Brutus, because he was a heavy chested, rather homely brute. He and one of his fillies were struck by lightning on the river bottom the week before the 2000 roundup.

Wind Canyon escaped the lightning but not the roundup that fall. He and his band were captured, but he was turned back out with three of his mares and two fillies.

The next roundup, in 2003, he was not so lucky. After that roundup, only three horses remained of the Wind Canyon band, Big Blue, who was the largest mare and one of the largest horses in the park at 16 hands, her bay roan overo son, and her loud bay overo colt. That colt, Little Shawn, a favorite of one of the temporary staff and named after him, was left behind when the rest of his band was run in with the helicopter. It was feared that he would not survive whatever caused him to be weak in his hind quarters or that he would be killed by a predator before his dam could find him after the roundup, but Big Blue found him and he recovered. He is no longer "Little" Shawn, because he has become a handsome big bachelor.

Big Blue refused to be taken by another stallion, so stayed with her young son, Wind Canyon II, who eventually became the band stallion. They had two offspring, one in '04 and one in '05 and added a new mare in '08.

Until the late 1990's, Wind Canyon ran unchallenged, but in 2000 a plain black stallion picked up a few of his mares and fillies. We called that stallion Black Brutus, because he was a heavy chested, rather homely brute. He and one of his fillies were struck by lightning on the river bottom the week before the 2000 roundup.

Wind Canyon escaped the lightning but not the roundup that fall. He and his band were captured, but he was turned back out with three of his mares and two fillies.

The next roundup, in 2003, he was not so lucky. After that roundup, only three horses remained of the Wind Canyon band, Big Blue, who was the largest mare and one of the largest horses in the park at 16 hands, her bay roan overo son, and her loud bay overo colt. That colt, Little Shawn, a favorite of one of the temporary staff and named after him, was left behind when the rest of his band was run in with the helicopter. It was feared that he would not survive whatever caused him to be weak in his hind quarters or that he would be killed by a predator before his dam could find him after the roundup, but Big Blue found him and he recovered. He is no longer "Little" Shawn, because he has become a handsome big bachelor.

Big Blue refused to be taken by another stallion, so stayed with her young son, Wind Canyon II, who eventually became the band stallion. They had two offspring, one in '04 and one in '05 and added a new mare in '08.

Saturday, August 9, 2008

The C and F Bands

These bands have both been fairly stable for the past 3-4 years. What makes them so interesting to observe is first, that the F band has a subordinate stallion as well as a band sire and second, that both the C and F bands and their three stallions have run together for the past several months. The three stallions keep control of their individual mares though the mares intermingle freely.

After the 2003 roundup, Singlefoot, ( F stallion) a four year old gray stallion, picked up most of the remaining mares that had run with Lindbo Blue in the Lindbo Flats/Boicourt Ridge area.

With Singlefoot are Lightning, a black overo mare, her loud colored daughter, Sweetheart, and several of their offspring. Sweetheart is so named because of a perfect black heart on her left side. Another older mare who has produced several foals for Singlefoot, is Frosty, a pretty bay roan.

In the spring of 2006 another gray stallion was observes following the band at a distance. As far as we know, he has never taken or bred any of Singlefoot's mares, but he continued to follow the band throughout that year and has become an accepted part of the band. Singlefoot never allows him to come in close contact with the other members of the band, but apparently has accepted him as a sort of body guard. When there are other stallions to be chased away or intruders to investigate, it is Satellite who does the work. Singlefoot stands calmly with his mares while Satellite chases off and threatening band stallions or bachelors.

Curiously the F band had two foals earlier this spring, but both were missing in May and their bodies were found in June. A new foal was born to Lightning in June.

Red Face ( C stallion) took control of what remained of band that Embers had once had. By the spring of 2006 several of that band were missing and Embers had joined the bachelors. Red Face is very protective of his mares and foals and always puts on a good show, running toward any intruders to check them out and then wheeling away to drive his band to safety.

With Red Face are Strawberry, a rather homely red roan overo, and Flame, his lead mare, a beautiful, big sorrel who has produced some pretty fillies. Two younger mares had come to him from the J band in the interior of the park. None of his mares had foaled as of July of this year.

After the 2003 roundup, Singlefoot, ( F stallion) a four year old gray stallion, picked up most of the remaining mares that had run with Lindbo Blue in the Lindbo Flats/Boicourt Ridge area.

With Singlefoot are Lightning, a black overo mare, her loud colored daughter, Sweetheart, and several of their offspring. Sweetheart is so named because of a perfect black heart on her left side. Another older mare who has produced several foals for Singlefoot, is Frosty, a pretty bay roan.

In the spring of 2006 another gray stallion was observes following the band at a distance. As far as we know, he has never taken or bred any of Singlefoot's mares, but he continued to follow the band throughout that year and has become an accepted part of the band. Singlefoot never allows him to come in close contact with the other members of the band, but apparently has accepted him as a sort of body guard. When there are other stallions to be chased away or intruders to investigate, it is Satellite who does the work. Singlefoot stands calmly with his mares while Satellite chases off and threatening band stallions or bachelors.

Curiously the F band had two foals earlier this spring, but both were missing in May and their bodies were found in June. A new foal was born to Lightning in June.

Red Face ( C stallion) took control of what remained of band that Embers had once had. By the spring of 2006 several of that band were missing and Embers had joined the bachelors. Red Face is very protective of his mares and foals and always puts on a good show, running toward any intruders to check them out and then wheeling away to drive his band to safety.

With Red Face are Strawberry, a rather homely red roan overo, and Flame, his lead mare, a beautiful, big sorrel who has produced some pretty fillies. Two younger mares had come to him from the J band in the interior of the park. None of his mares had foaled as of July of this year.

Thursday, July 24, 2008

The B and N bands

The B band has roamed in the area between Interstate 94 and the south side of the park's loop road for decades, but because of their insistence on remaining in their territory and an apparent inability of stallions from other parts of the park to gain any mares in that area, the band had suffered from inbreeding more than the bands that intermingled in the rest of the park. Several of the Interstate band were culled over the years because of obvious conformation faults. In the 2000 roundup, Interestate Blue was removed because he had been the band sire for several years and produced many offspring.

In the spring of 2001, Little Sorrel, a young bachelor son of a stallion that had run in the interior of the park, collected most of the remaining mares in that area and also acquired some of the mares that remained from his sire's band. Another young stallion, originally from the Interstate band, that had run on Johnson Plateau until he was strong and mature enough, picked up mares from those same bands and established his own small band in the same area but farther to the west. Gary, a gray, became the patriarch of the gray, N band, which is often referred to by the park personnel as the "Caspers." The Rose Gray Mare and Ghost are two of the oldest mares in the park.

Little Sorrel now has the largest band in the park (18), consisting of two older mares, Grandma Roan and Tanker, two younger mares, Trouble's Girl and Gary's Gray, and generations of their offspring. The lead mare, Grandma Roan, is getting old, but still produced some of the nicest foals in the band. Her striking bay roan stud colt is one of the five new foals this year.

In the spring of 2001, Little Sorrel, a young bachelor son of a stallion that had run in the interior of the park, collected most of the remaining mares in that area and also acquired some of the mares that remained from his sire's band. Another young stallion, originally from the Interstate band, that had run on Johnson Plateau until he was strong and mature enough, picked up mares from those same bands and established his own small band in the same area but farther to the west. Gary, a gray, became the patriarch of the gray, N band, which is often referred to by the park personnel as the "Caspers." The Rose Gray Mare and Ghost are two of the oldest mares in the park.

Little Sorrel now has the largest band in the park (18), consisting of two older mares, Grandma Roan and Tanker, two younger mares, Trouble's Girl and Gary's Gray, and generations of their offspring. The lead mare, Grandma Roan, is getting old, but still produced some of the nicest foals in the band. Her striking bay roan stud colt is one of the five new foals this year.

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

The A Band

Tom Tescher, the rancher who recorded the horses for 50 years, developed a system for keeping track of the different bands and individual horses. Tom is not able to keep his detailed, hand written records any more, but I have continued his system because it works.

In Tom's system each band is given a letter, so first I will tell you about the A band. For the past 10 years Curious George, pictured below, has had the A band, which could be seen along the east side of the Little Missouri River, the high ground between Jones and Paddock creeks and the Paddock Creek valley. Though he carefully guarded his band from other band stallions and bachelors that would have stolen his mares, he allowed park visitors to observe and photograph the band regularly, sometimes blocking traffic as they tried to escape from the pesky flies. He has been one of the most photographed and remembered horses in the park during those years because of his unique overo spots, bald face, and amicable nature.

He created a small band of young fillies in his forth year, but lost most of them to the 2000 roundup. Since then he has acquired and stayed with the same three mares for several years. Flicka, his lead mare, joined him as a two year old and bore him a foal every year for the past eight years. Stormy spent a winter across the river after her sire and another one of his fillies were struck by lightning a few days before the 2000 roundup. She found her way back across the river that spring and delivered a stout, flashy filly who became one of Curious George's favorites. Chubby could always be found hanging around him, while Stormy made his life difficult with her cantankerous disposition.

The offspring of those three mares populated the river valley and produced additional traditional and bachelor bands. One of Curious George's most popular offspring is his loud black and white overo, Circus, who had his own band for a short while, but now remains a bachelor.

Sadly, Curious George lost his band to two other stallions this spring. He can still be seen in the Paddock Creek area and occasionally on the river bottoms hanging out with other bachelor stallions. He has regained his rich brown, shiny coat, but he has lost the proud look in his eyes.

Most of his band now runs with one of his grandsons we have named Silver. Stormy, who gave Curious George so much trouble, seems to be quite content running with a younger stallion who was also frightened across the river by the storm in the fall of 2000.

Stormy and Chubby produced healthy stud colts this year while Flicka appears to be open for the first time. Her filly from 2001, Big Red, the only daughter Curious George kept, has also not foaled. Look for photos of this band soon, at the bottom of the posts.

In Tom's system each band is given a letter, so first I will tell you about the A band. For the past 10 years Curious George, pictured below, has had the A band, which could be seen along the east side of the Little Missouri River, the high ground between Jones and Paddock creeks and the Paddock Creek valley. Though he carefully guarded his band from other band stallions and bachelors that would have stolen his mares, he allowed park visitors to observe and photograph the band regularly, sometimes blocking traffic as they tried to escape from the pesky flies. He has been one of the most photographed and remembered horses in the park during those years because of his unique overo spots, bald face, and amicable nature.

He created a small band of young fillies in his forth year, but lost most of them to the 2000 roundup. Since then he has acquired and stayed with the same three mares for several years. Flicka, his lead mare, joined him as a two year old and bore him a foal every year for the past eight years. Stormy spent a winter across the river after her sire and another one of his fillies were struck by lightning a few days before the 2000 roundup. She found her way back across the river that spring and delivered a stout, flashy filly who became one of Curious George's favorites. Chubby could always be found hanging around him, while Stormy made his life difficult with her cantankerous disposition.

The offspring of those three mares populated the river valley and produced additional traditional and bachelor bands. One of Curious George's most popular offspring is his loud black and white overo, Circus, who had his own band for a short while, but now remains a bachelor.

Sadly, Curious George lost his band to two other stallions this spring. He can still be seen in the Paddock Creek area and occasionally on the river bottoms hanging out with other bachelor stallions. He has regained his rich brown, shiny coat, but he has lost the proud look in his eyes.

Most of his band now runs with one of his grandsons we have named Silver. Stormy, who gave Curious George so much trouble, seems to be quite content running with a younger stallion who was also frightened across the river by the storm in the fall of 2000.

Stormy and Chubby produced healthy stud colts this year while Flicka appears to be open for the first time. Her filly from 2001, Big Red, the only daughter Curious George kept, has also not foaled. Look for photos of this band soon, at the bottom of the posts.

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Current TRNP Horses

Sine the 2003 roundup, when over 70 horses were sold and 57 horses were left in the Park, their numbers have steadily grown. Last fall, a roundup was attempted, but failed due to the crash of the helicopter. No one was seriously injured, but it brought the roundup to an abrupt halt, and no horses were sold. At that time there were 127 horses of various ages. Two foals were born shortly before the mid-October roundup and one was born a week or two after. They all survived the winter.

After tracking the horses in May, June, and July, we have determined that there are approximately 135 horses in the park as of July 15th. We may still have additional foals as the summer progresses. Some adults and three foals have died since last fall and a band of 10 horses was removed in early May by a low stress livestock handler. (This story will be coming soon.)

In the next several weeks, I will attempt to introduce you to each of the 14 bands, their band stallions, lead mares, other band members, and the 14 new foals. There are also around 25 bachelor stallions roaming in loosely united bands and individually. Many of these horses have their own unique stories, so come back often to meet the wild horses of TRNP.

After tracking the horses in May, June, and July, we have determined that there are approximately 135 horses in the park as of July 15th. We may still have additional foals as the summer progresses. Some adults and three foals have died since last fall and a band of 10 horses was removed in early May by a low stress livestock handler. (This story will be coming soon.)

In the next several weeks, I will attempt to introduce you to each of the 14 bands, their band stallions, lead mares, other band members, and the 14 new foals. There are also around 25 bachelor stallions roaming in loosely united bands and individually. Many of these horses have their own unique stories, so come back often to meet the wild horses of TRNP.

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

WILD HORSES OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT NATIONAL PARK

The horses running wild in Theodore Roosevelt National Park in western North Dakota have developed over the years into a breed unlike any other. Descendants of sturdy domestic farm horses, trusty ranch stock and the ponies that carried our Native American people across the plains, they have survived harsh North Dakota blizzards, temperatures of -40 degrees, and the scorching sun and hot dry winds of summer. They have learned to find shelter in the washes and Juniper stands of the badlands and drink from the water filled tracks of Bison after a sudden summer rain.

In the mid 1900's many wanted them dead. Hundreds were herded into rail cars and shipped away to slaughter when trains, autos, and tractors made them obsolete. Cowboys and ranchers made sport of running them down or shooting them to keep them from foraging on the rich, but often sparse grasses of the Little Missouri breaks. Early roundups were conducted on horseback, by pickup truck, and even with planes. It didn't much matter what happened to the horses during the wild chase, since they were destined for destruction anyway.

The horses that remained in the national park, once it was fenced, were the lucky ones. For many years they too were targeted for removal as trespass animals, but some survived and became the foundation of these proud and beautiful horses that call the North Dakota badlands their home.

These horses had a friend in a local rancher, who loved them, kept track of them, and managed them for decades. His story will becoming to this blog soon.

In the mid 1900's many wanted them dead. Hundreds were herded into rail cars and shipped away to slaughter when trains, autos, and tractors made them obsolete. Cowboys and ranchers made sport of running them down or shooting them to keep them from foraging on the rich, but often sparse grasses of the Little Missouri breaks. Early roundups were conducted on horseback, by pickup truck, and even with planes. It didn't much matter what happened to the horses during the wild chase, since they were destined for destruction anyway.

The horses that remained in the national park, once it was fenced, were the lucky ones. For many years they too were targeted for removal as trespass animals, but some survived and became the foundation of these proud and beautiful horses that call the North Dakota badlands their home.

These horses had a friend in a local rancher, who loved them, kept track of them, and managed them for decades. His story will becoming to this blog soon.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)